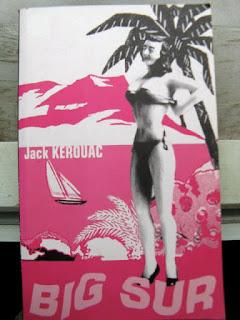

Hello attic! Where did you get to? Or rather, where did I go? (I think I may have wandered away somewhere.) But now that you're here, I feel I must bring a book (toil, toil, up the ladder) that I've been meaning to put in the attic for some time.

Nice, eh.

Provenance: bought at Robin Downs Bookshop, Murwillumbah (now defunct, I imagine) in the 1970s for 90 cents. Previously at Higgs Bookshop Sydney for 50 cents.

A year or so ago I bought another second-hand copy at the famous (to me) Canty's bookshop in Fyshwick, Canberra ($7.50), and the words are just the same, the cover even more tasteless:

Which is the remarkable thing about books. I mean that the words are the same ... I thought I would only ever be able to read my wonderful old copy, and it was falling apart (as books do), and then where would I be? But this new copy is just as good, words wise, though I am less attached to it as artefact.

Now, Kerouac is always being lambasted for being sexist etc etc and who am I to argue otherwise?

But I present to you this:

(Kerouac is at Ferlinghetti's cabin at Bixby Canyon, though he says it's as Big Sur: Jean Louis always made laughable attempts to fictionalise his books ...)

___ So once again I'm Ti Jean the Child, playing, sewing patches, cooking suppers, washing dishes (always kept the kettle boiling on the fire and anytime dishes needed to be washed I just pour hot water into the pan with Tide soap and soak them good and then wipe them clean after scouring with a little 5- &-10 wire scourer) --- Long nights simply thinking about the usefulness of that little wire scourer, those little yellow copper things you buy in supermarkets for 10 cents, all to me infinitely more interesting than the stupid and senseless 'Steppenwolf' novel in the shack which I read with a shrug [...]

Kerouac, Big Sur, Chapter 7

I rest my case. The poetry of kitchens, written by a man.

(And I often think of the infinite pleasure I've had from this little falling-apart book, bought for 90 cents over 30 years ago.)